La scoperta di Urano - The discovery of Uranus

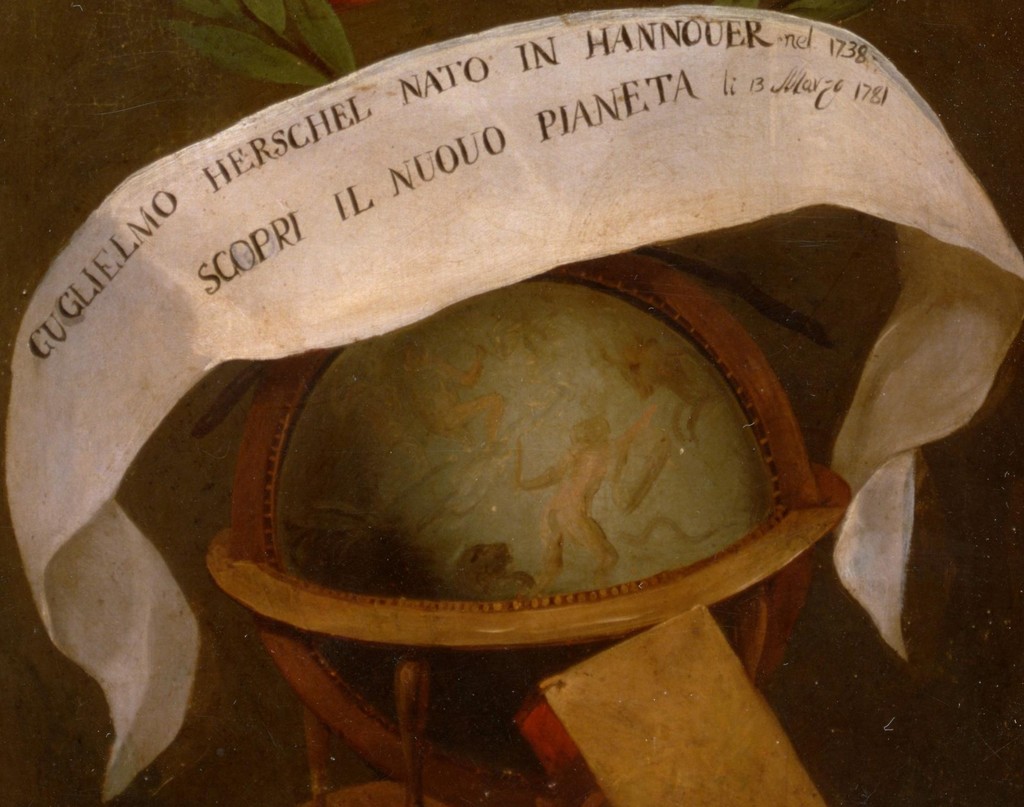

Particolare del cartiglio con il globo celeste.

Dettaglio del Ritratto di William Herschel, G. Velasco, 1791.

Era la notte del 13 marzo 1781 quando, impegnato nelle osservazioni di stelle doppie con il telescopio riflettore da lui realizzato, William Herschel scorse nel cielo un punto luminoso che attirò particolarmente la sua attenzione. Ciò che fino ad allora era già stato osservato e classificato come stella debolmente luminosa, infatti, agli occhi di Herschel doveva essere qualcosa di diverso poiché ne aveva intuito il moto proprio. Non comprese subito che si trattava di un pianeta e inizialmente gli attribuì la natura di cometa, cui diede il nome di Georgium Sidus, in onore di re Giorgio III. Solo due anni anni dopo fu provato che si trattava di un pianeta che Herschel volle battezzare Georgian Planet. Il sovrano, per premiare il giovane astronomo per l’importante scoperta fatta e per la fama meritata, lo nominò Astronomo personale del Re, creando per lui una nuova carica, diversa da quella già esistente di Astronomo Reale ricoperta dal collega Nevil Maskelyne, e donò ad Herschel una ricca somma di denaro per proseguire i suoi studi e realizzare telescopi sempre più sofisticati.

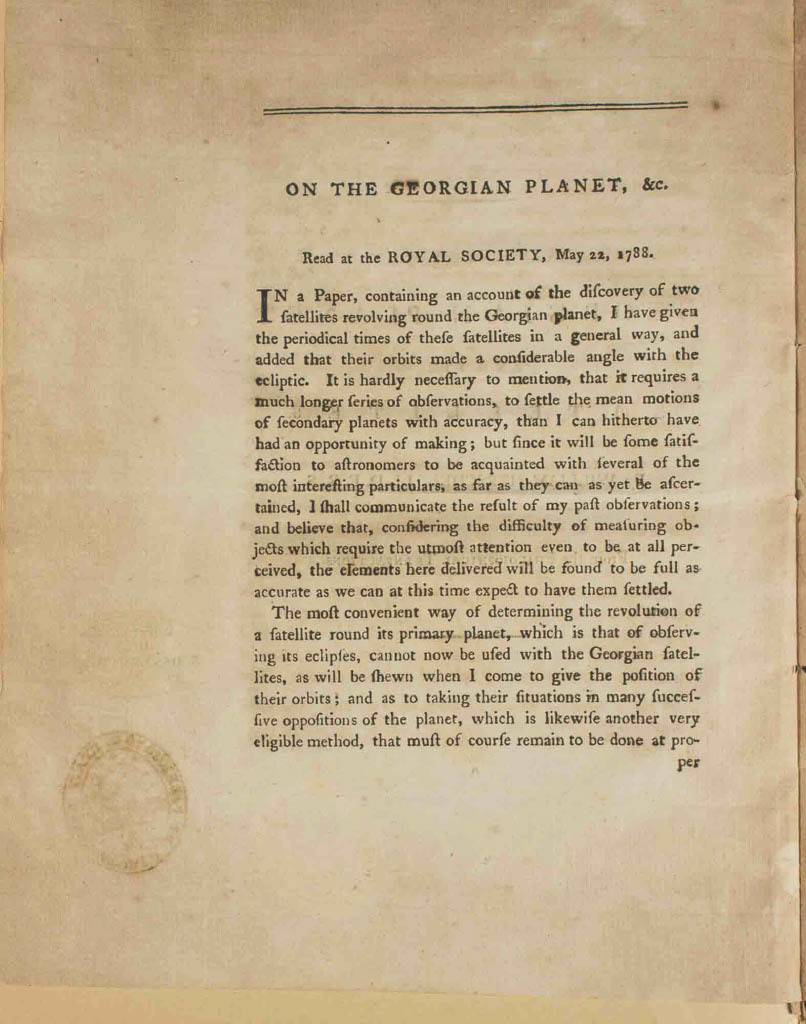

W. Herschel, On the Georgian planet and its satellites, «Philosophical Transactions», 78, 1788, in Miscellanea Herschel.

Del nuovo pianeta e dei suoi due satelliti, Titania e Oberon, scoperti dallo stesso astronomo nel 1787, Herschel trattò in una pubblicazione, On the Georgian planet and its satellites, edita nel 1788 tra le pagine delle «Philosophical Transactions», e conservata presso l’Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo all’interno di una miscellanea che raccoglie alcuni suoi lavori. Il nome di Georgian planet, accolto con entusiasmo da parte del mondo anglosassone, fu però rifiutato dal resto della comunità scientifica che suggerì varie alternative: su iniziativa del celebre astronomo dell’Osservatorio di Parigi Jérôme de Lalande, fu avanzata la proposta, accettata dai colleghi francesi, di chiamare il nuovo pianeta con il nome del suo scopritore: Herschel. Non stupisce, pertanto, che Urano compaia proprio con questo appellativo nel planetario custodito presso il Museo della Specola di Palermo, costruito nei primi decenni dell'Ottocento dal meccanico locale Giuseppe Porcasi su disegno di Piazzi quale strumento didattico, e che riporta, sulla carta incollata e possibilmente realizzata dallo stesso Lalande, tutte le iscrizioni in francese. Al termine del dibattito scientifico internazionale, a prevalere fu il nome di Urano, dio greco del cielo, proposto da Bode e, infine, ampiamente condiviso anche dagli astronomi inglesi.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

It was the night of March 13, 1781 when William Herschel, engaged in observing double stars with his reflecting telescope, saw a bright point in the sky that particularly attracted his attention. What until then had already been observed and classified as a faintly bright star, in fact, in Herschel's eyes must have been something different since he had guessed its proper motion. He did not immediately understand that it was a planet and initially attributed the nature of a comet to it, which he gave the name of Georgium Sidus, in honor of King George III. Only two years later it was proved that it was a planet that Herschel wanted to call Georgian Planet. The sovereign, to reward the young astronomer for his important discovery, appointed him Personal Astronomer of the King, creating for him a new position, different from the existing one of Royal Astronomer held by his colleague Nevil Maskelyne, and donated to Herschel a large sum of money to continue his studies and build increasingly sophisticated telescopes.

W. Herschel, On the Georgian planet and its satellites, «Philosophical Transactions», 78, 1788, in Herschel Miscellaneous.

About the new planet and its two satellites, Titania and Oberon, discovered by the same astronomer in 1787, Herschel treated in a publication, On the Georgian planet and its satellites, published in 1788 between the pages of the "Philosophical Transactions", and preserved at the Palermo Astronomical Observatory within a miscellany that collects some of his works (Herschel Miscellaneous). The name of Georgian planet, welcomed with enthusiasm by the Anglo-Saxon world, was however rejected by the rest of the scientific community which suggested various alternatives: on the initiative of the famous astronomer of the Paris Observatory Jérôme de Lalande, the proposal was put forward, accepted by French colleagues, to call the new planet after its discoverer: Herschel. It is not surprising, therefore, that Uranus appears with this name in the planetarium kept at the Museo della Specola in Palermo. It was made in the early decades of the Nineteenth century by the local mechanic Giuseppe Porcasi on a design by Piazzi and reports, on the glued paper and presumably made by Lalande himself, all inscriptions in French. At the end of the international scientific debate, the name of Uranus, the Greek god of the sky, proposed by Bode and finally widely shared by English astronomers, prevailed.